5 Ear Training Exercises for Violin

/How do you play in tune on the violin? How do you develop good intonation? How can you even tell if you are too sharp, too flat, or perfect? These ear training exercises for the violin will help your ear hear the slight subtleties in music and help you play better in tune!

With fretted or keyed instruments, you can get away with putting your finger down and not really listening to the quality of the note you are producing. As long as the instrument is in tune and you placed your finger on the correct key or fret, the note you are trying to play should be in tune. Not so with the violin! Since there are no keys or frets, your ear has to be in control. Muscle memory alone won’t cut it. Your ear must tell your finger if the note you just played was too high, too low, or just right. And to do that, your ear has to be the boss when you are playing violin.

This is a hard concept for many students to learn. Students generally focus on their left hand fingers and let their fingers try to control the show. But to truly master the violin, your fingers must be lowly employees to the CEO—the ear!

For most of us, our ears aren’t natural born leaders. You have to teach your ear how to take over. Here are some exercises to help your ear listen better.

1. Pitch matching

Do this first without an instrument at all. When you hear a note from a song, try to match it. Either sing it, hum it, or whistle it. You can do this in the car while listening to music. You can also try playing a random note on a piano or on your violin and try to replicate it with your choice or vocal replication (singing, whistling, of humming).

Now try the same concept, but with the violin. You don’t have to worry about playing the note with the “correct fingering.” Use any finger you want to achieve the correct pitch. Try to sing a random pitch and then find where it exists on the violin. One way is to simply put your finger on a string and start sliding it around until you find the pitch you are looking for. You will discover that one note can exist on several different strings.

2. Identify if music ascends or descends

This is just a listening exercises. As you listen to music, try to determine when the music is going up and when it is going down. While this sounds easy, it might be harder than you think.

Sing one of your favorite songs, move your hand up and down depending on whether the next note in the song goes up, goes down, or stays the same.

3. Identify skips and steps

Another listening exercise. As you listen to music, determine if the notes are moving by step—one note after another like a scale (A B C D) or by skips (A C E).

4. Learn what intervals sound like

Intervals are those skips between notes. We can measure the distance between notes using intervals. A to B is the interval of a second (always start counting with the bottom note). A to C is a third. C to the next highest C is an octave—8 steps.

Each interval has a certain sound and it’s easiest to associate that interval with a song. For instance A to B is a second (a major second to be specific) and it sounds like the first two notes of Happy Birthday. C to C is an octave and sounds like Somewhere Over the Rainbow. Listen for the first two notes in the word “somewhere.”

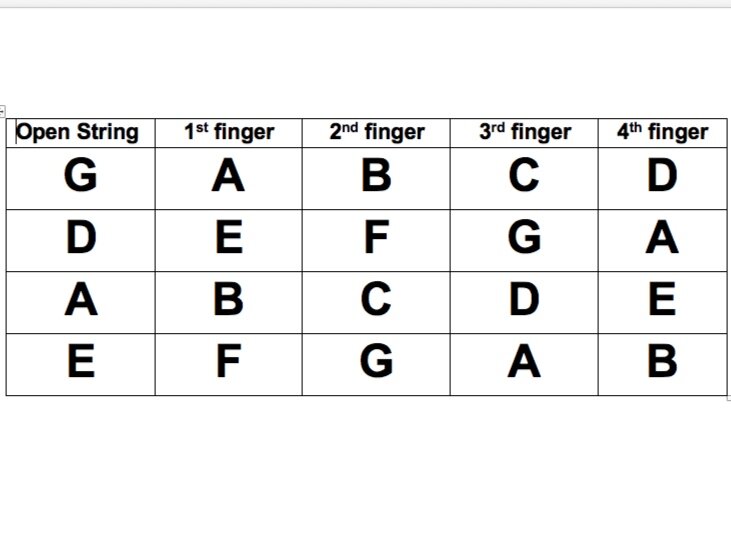

Use this chart to help you choose songs to be able to identify each of the intervals. As you learn them, you will be able to hear intervals in the music you listen to and the music you play.

5. Try to play simple songs on the violin without using music

This exercises is not only great for your ear, it’s lots of fun. Once you develop this skill, you won’t have to spend hours searching the internet for sheet music to your favorite song, you’ll be able to pick out the notes yourself.

You’re going to use all those other skills we just talked about. First, you’re going to have to pitch match. Sing the note that your song starts on and try to find that on the violin. Next, decide if you are going to have to go up for the next note or down? Or maybe you’ll stay on that same note? If you do move up or down, are you moving by step or by skip? If you are moving by skip, by what interval? Once you determine what the interval is, you’ll know what note comes next.

Do these steps for every note in the song. Eventually, with enough practice, your fingers will start to know what note comes next.

Start off with simple folk songs or hymns. These songs generally don’t skip around a lot so it’s easy to pick them out by ear.

You are never too good for this exercise! As you progress, pick harder and harder songs to play by ear. Since you aren’t looking at music, doing this exercises leaves your ear no choice but to take over!

Practice these skills everyday, with the instrument or without it. The more you exercise your ear, the better it will be able to hear small details and variations in pitch. You’ll know if you’re playing a note too sharp or too flat. Your ear will tell you! Once you let your ear be the boss, it will turn into a little tyrant—but that’s a good thing!

Happy Practicing!