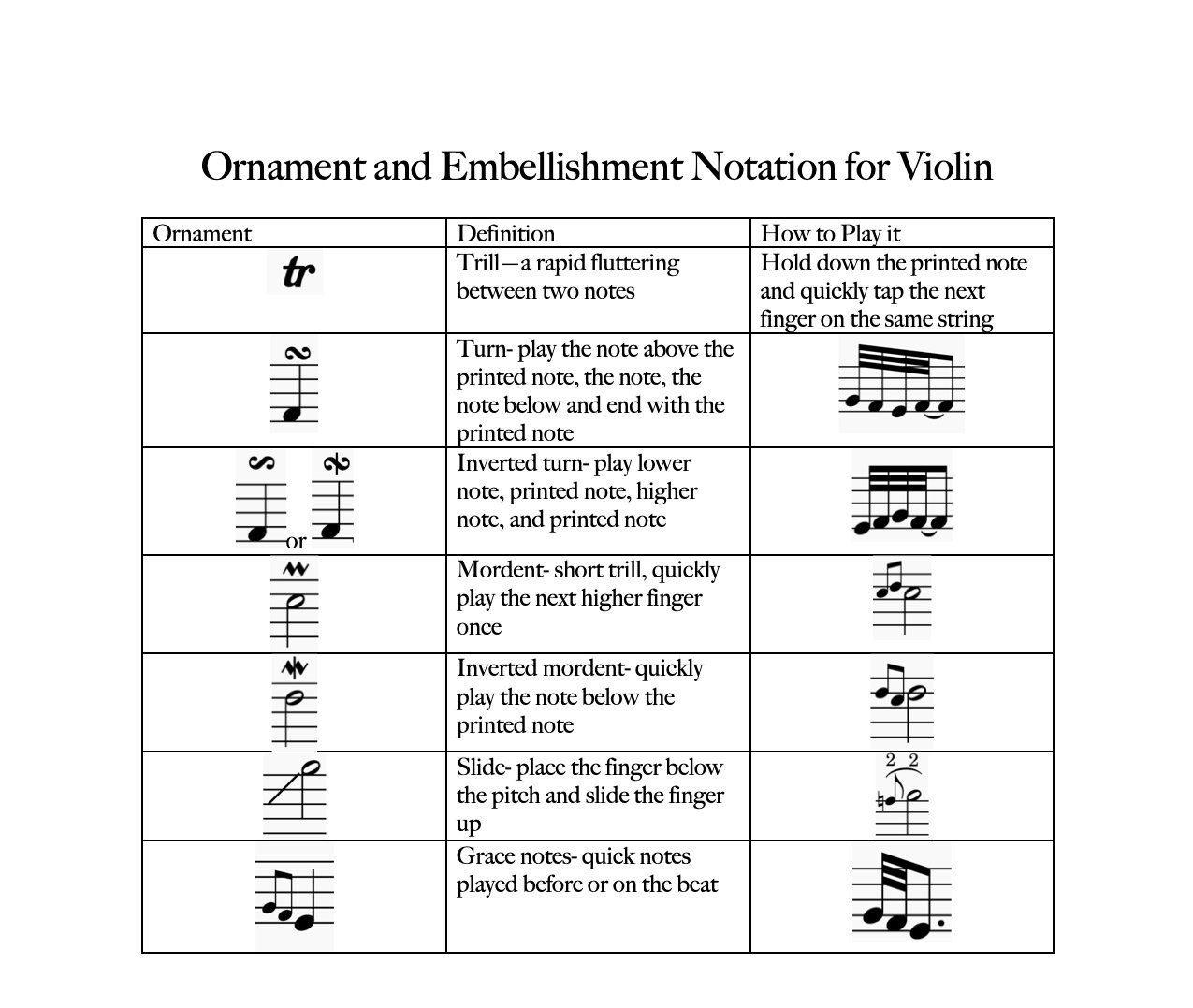

Trills, Turns, Mordents, Slides, and Grace Notes (Common Violin Ornaments Explained)

/If you’ve ever seen a sideways “S” in music or maybe some squigglies above a note, you’ve run into some violin ornaments or embellishments. Not to worry! These crazy looking symbols aren’t that hard to understand. I’ve identified the 5 most common violin ornaments you will see in classical violin music and fiddle music. Get ready to finally understand trills, turns, mordents, slides and grace notes in violin music!

Want to Download and Print This Ornaments for Violin Chart?

Just click here to print out this free chart!

How to Play a Trill on the Violin

Trills in violin music are notated with a “tr” over the note. To play a trill on the violin, simply hold down the main note that is printed and rapidly tap the next higher note. So if you have a trill over an F#, 2nd finger on the D string, you would rapidly tap the 3rd finger G while holding the F# down. This will make the trill sound like a bird trilling or a flutter. You can start slow and gradually speed up tapping the next higher note.

What is a Sideways S in Violin Music? A Turn!

You will often see some funny-looking sideways S’s in violin music. That’s a turn. How do you play a turn on the violin? It’s not as difficult as it seems.

If the turn is over an F, you would start on the note above the printed note, then play the actual printed noted, then go one step below the printed note, then back up to the printed note. Once you practice turns on the violin a few times, you will get the feel for what they sound like.

But sometimes the S is reversed, or sometimes the sideways S has a slash through it. That’s an inverted turn.

It goes the opposite direction of the normal turn. Start one note below the printed note, go up to the printed note, keep going one more note above the printed note, then back down to the printed note.

Remember, whether it’s a regular turn or an inverted turn, you always end on the printed note. What changes is what note you start on.

How Do I Play a Mordent in Violin Music?

First of all, what is a mordent!? Well it looks like a squiggle above a note. Like this.

See how it kinda of looks like an “m.” Use that to help you remember “mordent".” You can think of a mordent in violin music like a min-trill. To play a mordent on the violin, all you do is quickly play the next higher note once and then return to the original printed note.

You also have inverted mordents. That’s the squiggle with a line through it like this.

To play an inverted mordent, you’ll just start on the printed note, go down one note and then back up to the printed note. Simple as that!

How to Play a Slide in Fiddle Music?

Slides are very common in fiddle music. A slide is notated by an angled line leading up to a note. Like this.

To play a slide on the violin, just place the finger about a half step below where you would normally place the finger then slide up into the printed note. Think of it like you accidentally played an out of tune note and you’re quickly sliding into the correct note and that’s a slide!

How to Play Grace Notes on the Violin

The last type of violin ornament we’ll talk about is a grace note. Graces notes can be single or multiple. Grace notes are the little notes before or after a normal, printed note. They can be played on the beat or before the beat.

Different Types of Grace Notes: Acciacatura and Appoggiatura

If the grace note has a slash through it, it’s technically called an acciacatura. Acciacatura means “crushed.” The acciaccatura or slashed grace note is played before the beat.

If the grace note doesn’t have a slash, it’s an appoggiatura. Appoggiaturas are played on the beat and essentially steal time from the main printed note. Appoggiaturas often have a sense of leaning on the grace note and resolving to the main printed note.

Those are the 5 most common ornaments and embellishments you’ll see in violin and fiddle music!

Do you want more music theory for the violin?

Check out my course on music theory for the violin. It’s over 6 and a half hours of helpful information on music theory! Everything you ever needed to know!

Happy Practicing!

.png](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/554545e3e4b0325625f33fa6/1509920162883-X31U76G5Y2ZW95957ZLB/Screenshot-2017-11-5+b3c9c739174d124e1bfdd1694c83d500--violin-fingering-chart-violin-music-sheets+jpg+%28JPEG+Image%2C+472+%C3%97+43%5B...%5D%281%29.png)

![10 Best Violins for Beginners: A Violin Teacher’s Ultimate Guide [2026]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/554545e3e4b0325625f33fa6/1600433065588-JQV56M1W9LNI833AVGEE/10+best+violins+for+beginners+2020.jpg)